Welcome to a business meeting of your two Ruffian Co-Artistic Directors:

Eva: Hi my friend!

Kaitlyn: Hey Evie B!

Eva: You’re so far away from me at the moment, all the way across the country.

Kaitlyn: Staring at the Rockies covered in mist this morning, very portentous. How’s TO?

Eva: I’m staring to the CN Tower covered in mist. So I guess we’re living in a pretty portentous world. [Eva quickly googles the definition of portentous]

Kaitlyn: We sure are.

Eva: I guess we should start considering what play to do this summer? Though this mist and this PORTENTOUS feeling is making me feel like it’s not summer at all.

Kaitlyn: It does feel like ‘Winter is coming…’. [this is not a plug for HBO]

Eva: Enough about seasons, Kaitlyn, we need to talk about what Shakespeare play we are doing.

Kaitlyn: “Now is the winter of our discontent.”

Eva: We did that one.

Kaitlyn: “Summer’s lease hath all too short a date.”

Eva: Kaitlyn, focus!

Kaitlyn: Nothing is ‘springing’ to mind….sorry.

Eva: I forgive you.

Kaitlyn: Exactly! Forgiveness!

Eva: It’s a powerful act. Some might say a magical act. Have you ever forgiven someone who really hurt you?

Kaitlyn: Yes, and it felt like the biggest release I’ve ever experienced.

Eva: Kind of like you were being released from stone?

Kaitlyn: After what felt like 16 years!

Eva: Was it hard to forgive?

Kaitlyn: I did it instinctually, in that instance, because it was hurting me to hold on to it. So I guess it was harder to hold onto than to forgive, but it took some time. I think our society is weary of forgiveness at the moment though, and maybe I am too?

Eva: I think that’s true. Do you think it’s connected to the fact that we don’t know how to properly repent?

Kaitlyn: Good question. Have you ever repented? Did you know how?

Eva: I have. It took longer than I wish it could have. I needed to really confront who I was, and my actions. That’s a terrifying thing to do. I don’t know if you feel this too, but don’t you think we live in a world where we can never be wrong?

Kaitlyn: I do feel that on a larger level, for anyone other than Donald Trump for some reason, but personally, I am wrong all the time, and somehow, you’re still my friend 🙂

Eva: Even when we have a country in between.

Kaitlyn: Exactly.

Eva: Are you thinking what I’m thinking?

Kaitlyn: Croissants!

Eva: And…

SHAKESPEARE IN THE RUFF IS PROUD TO PRESENT,

with the generous support of Crow’s Theatre:

THE WINTER’S TALE

Shakespeare’s magical dive into repentance & forgiveness

Directed by Sarah Kitz

Kaitlyn & Eva: Oh hey Sarah! Fancy seeing you here. Why do you think The Winter’s Tale is perfect for today?

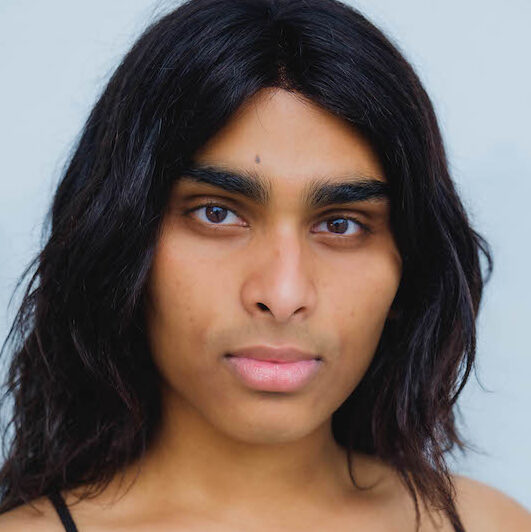

Sarah Kitz. Photo by Alejandro Santiago

Sarah: Hi Kaitlyn & Eva! Thanks for having me! It’s very fancy to be here!

The Winter’s Tale is a play for us now. It is a fairy tale (improbable things happen), which is another way of saying it is a myth about humanity. Fairy tales are not escapism but doors in the floor into the basement of the human psyche. Isn’t it the perfect time to have a show where we plumb the depths of patriarchy with an eye to coming out the other side by listening to and believing women? And isn’t it interesting to do that on a human artifact that’s hundred of years old, which has been used as a tool of colonialism, which is a container for so many conflicted feelings, to which we owe no undue reverence, which we will bash about to see what is has to say to us now.

This play is also an investigation of inheritance. In a culture that doesn’t know what it has to pass on, and a younger generation that has been violently disinherited and doesn’t know what is rightfully theirs, the intergenerational relationship is one of anxiety.

Eva: Kaitlyn! Maybe we should also tell folks who’s playing Paulina!

Kaitlyn: I think it’s too early for that.

Eva: But it’s so fun!

Kaitlyn: In a month we can announce the whole cast, so let’s not say any-

SHAKESPEARE IN THE RUFF IS MEGA-PROUD TO PRESENT,

with the generous support of Crow’s Theatre (K: cool! what’s this all about? E: tune in next week to find out)

THE WINTER’S TALE

Shakespeare’s magical dive into repentance & forgiveness, and some bad-ass ladies

Directed by Sarah Kitz

And featuring JANI LAUZON as Paulina!

Kaitlyn & Eva: Jani! Welcome! Why are you excited about this play and this part?

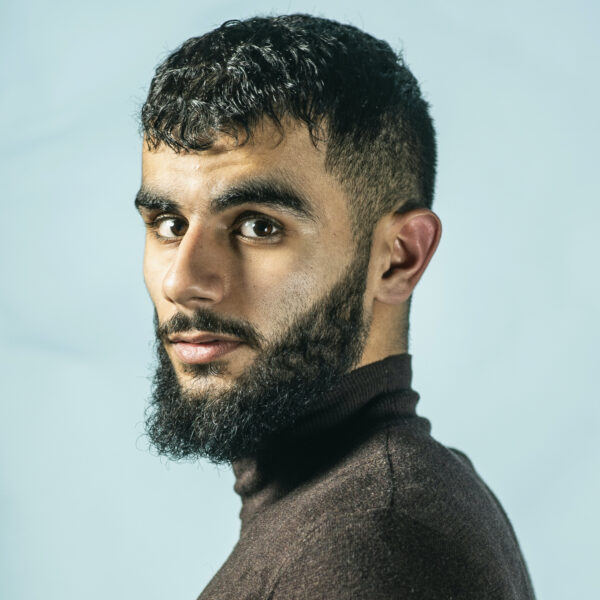

Jani Lauzon, photo by Helen Tansey

Jani: I am a Shakespeare junky. Love every opportunity to perform his text. As for The Winter’s Tale, the play is so beautifully written and grounded in what is also a modern theme, the poisonous, disastrous emotion of jealousy that breaks down all possibilities of being in right relationship with each other. I am also fascinated by the metaphor of stone and it’s consequence when our hearts are shunned, shut down, and silenced. I understand that well having been through it in my life. As for Paulina, she is a woman who refuses to be ruled, she has a “truth-telling tongue”. She is called many things as a result: “bawd”, “hag”, “crone”, mankind witch”. But Paulina refuses to play the part assigned to her. Women in this play are on trial, through the character of Hermione. As she is often referred to as “grace”, it is grace itself that has been turned to stone. Paulina uses her magic to bring grace back into the world. Besides, playing Paulina has been on my bucket list for many years. This gives me the opportunity to cross that one off the list!

Eva & Kaitlyn: You were in a production by Shakespeare in the Rough, the company that used to perform in Withrow Park. How do you feel about returning to Withrow Park for another summer?

Jani: I am really looking forward to being back in the park. It was such an honour to play Shylock in Merchant of Venice surrounded by the trees, the bats, and the amazing, warm and supportive audiences that attend. I want to continue to be the kind of artist who has something to learn. Rehearsing in the park, playing outside and reaching audiences that are genuinely interested in this kind of theatre experience keep me humble as an actor. I don’t want to ever loose that.

Kaitlyn: I’m pretty excited, Eva. I wish it were summer already!

Eva: No no, I wish it were WINTER.

THE WINTER’S TALE coming to Withrow Park August 2019