We wrote a shakespeare play. A story that is filled with epic-ness, and heartbreak, and poetry, and laughter, and verse, and joy and tragedy. A play that is not an adaptation, or a retelling of shakespeare— because it is shakespeare.

We wrote a shakespeare play. A story that is filled with epic-ness, and heartbreak, and poetry, and laughter, and verse, and joy and tragedy. A play that is not an adaptation, or a retelling of shakespeare— because it is shakespeare.

For 10 years, the Young Ruffian Apprenticeship Program has welcomed exciting new creators, and this year is absolutely no different!

Led by Desirée Leverenz and Education Coordinator Makram Ayache, this year’s program is a paid 4-week creation course, where participants from across Ontario are gaining skills in diverse creation methods, creating solo pieces as well as ensemble pieces, and interrogating play structure and content creation. They are learning the rules of creation and daring to break them as they discover, uplift, and amplify their own unique and vital theatrical voices.

Alongside creating with Desirée, participants are being mentored by artists Kwaku Okyere, Jeff Yung, Maddie Bautista, Jeff Ho and Erum Khan.

Check out these amazing artists and their work live on July 30th from 5:30pm to 8pm. This is an informal sharing session where we will share stories, poetry, films and be in conversation with the audience. Email Desirée for the zoom link!

Marco DeLuca

Marco DeLuca is an actor, singer, dancer and creator living in Oakville, Ontario and hails from Treaty Six. He will be entering his final year in the Bachelor of Music Theatre Performance Program at Sheridan College in the fall of 2021 and is thrilled to be an administrative assistant and team member for Sheridan College’s Expanding the Lens Diversity and Inclusion initiative. Marco is always eager and thrilled to continue honing his craft through writing and creation. In his work, Marco hopes to inspire and elevate community passion through impactful and delicate stories that encourage and embrace individuality and authenticity.

Ericka Leobrera

Ericka is a Philippine-born multi- and inter-disciplinary performer and creator. As a storyteller, their imagination manifests itself in more ways than one. In creation, Ericka intertwines various artistic practices; playwrighting, physical theatre, movement, dance, poetry, and sound. Ericka is a graduate of Humber College’s Theatre Arts – Performance program where they trained in devised and physical theatre. Selected theatre credits include: TomorrowLove (dir. Christopher Stanton), Elektra (dir. Richard Greenblatt), Through The Bamboo (dir. Nina Lee Aquino), Odd Ones Out (dir, Herbie Barnes)

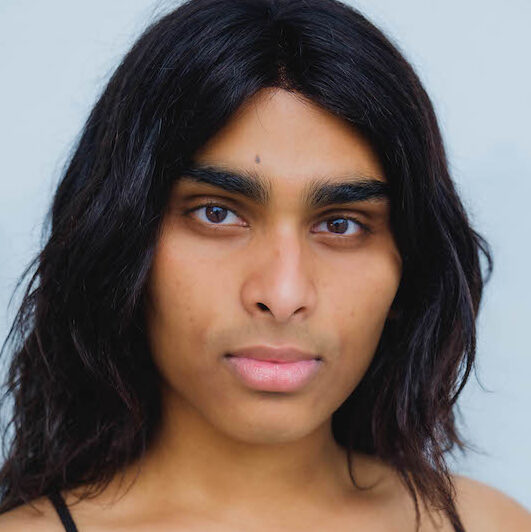

Kiara-Kumail

Kiara-Kumail is a South Asian trans-feminine actor and artist from Tanzania. They currently study Performance Acting at what is now called X-University. Their most recent-credits include Wanda Murley in the radio-play Can’t See Home From Here at the Pocket Festival. They also have experience with classical Shakespearean texts such as their performance of Falstaff in King Henry IV Part 1. They are committed to telling stories from a decolonized, queer and racialized perspective to liberate marginalized voices. They have a profound interest in uncovering the mysteries of the deep sea and the creatures that lie within.

Sid Malcolm

Sid Malcolm is a recent graduate from Brock University, Hons. BA in Dramatic Arts with a minor in Music. Sid has a passion for the world of production and performance with a new found desire to explore storytelling.

She has been able to pursue production as the Assistant Technical Director to three consecutive shows at Brock. Most recently, she had the pleasure of directing, devising, and performing in anthology piece Ouroboros (2021)

Sid has a passion for sharing truths and combining stories of injustice with theatre. She strives to create art which questions the practices that are considered normal in day to day life.

Summer Mahmud

Summer is a Queer writer, director, actor & musician, and fresh graduate of McGill University. They are currently a Writer-in-Development at Teesri Duniya Theatre in Montreal, and an Artistic Associate at Theatre Artaud. Previously, they have worked as Art Director & Curator at Tuesday Night Cafe Theatre, and have played multiple concerts across Pakistan & Canada. Summer is interested in the malleability of form and the absurdity of being[;] anything at all.

Are you an emerging artist who wants to keep in the know about all our educational programs and opportunities? Join our mailing list today!

Are you someone who wants to support paid educational opportunities, like the Young Ruffian Apprenticeship Program, and keep them available for future generations? Make a charitable donation and help us support emerging voices!

On behalf of the Board of Directors, it is my pleasure to announce the incoming leadership of Shakespeare in the Ruff: Patricia Allison, Christine Horne, Kwaku Okyere, PJ Prudat, and Jeff Yung. These incredible leaders have experience on stage, behind the scenes, and in the audience of Shakespeare in the Ruff. Their creativity, community-mindedness, and compassion make them the undeniable leaders of this company.

Since the announcement of Kaitlyn Riordan and Eva Barrie stepping down as Ruff’s leadership, the Leadership Search Committee has worked diligently and embedded Ruff’s five key values (creative audacity, anti-racism & decolonized practice, accessibility, education & mentorship, and respect) into the entire search and hiring process. The Leadership Search Committee consisted of of board members Dasha Peregoudova, Cecile Peterkin, and Joseph Zita, and Ruff community members Rachel Forbes and Miquelon Rodriguez. For their dedication to the future of this company, we thank them.

The board is excited for the new leadership to take the reins of Shakespeare in the Ruff in November 2021. We have had ten amazing years, where Kaitlyn and Eva have taken the company from inception to an institution in Withrow Park. There is no doubt in my mind, and in my heart, that the new leadership will continue the creative audacity to rediscover the work of Shakespeare that will break boundaries and move the community forward

— Fernando Alfaro, Chair of the Shakespeare in the Ruff Board of Directors

Patricia Allison (she/her) is a queer/ disabled choreographer and movement director. She comes from a contemporary dance background and spent a significant time studying canonical-counter discourse. Patricia lives with her wife and two birds named Larry and Wilbur who enjoy sitting on her shoulder while she types (the birds, not her wife).

Christine Horne (she/her) is a mother and actor, last seen on stage as Hamlet in Why Not Theatre’s Prince Hamlet. She’s a fledgling gardener, excitable bird watcher, and avid reader aloud of children’s literature. Christine has received several awards for her work in theatre, television, and film, but she holds none so dear as when she was crowned The Queen of Weird Shakespeare by a passing cyclist while rehearsing Ruff’s Portia’s Julius Caesar.

Kwaku Okyere (he/him) is a queer Ghanaian-Canadian multidisciplinary theatre artist. Most recently, Kwaku played Oberon in the Dora-nominated ensemble of Theatre Rusticle’s acclaimed swan song production of Shakespeare’s Midsummer Night’s Dream, performed at Buddies in Bad Times Theatre, which recently presented Kwaku with the 2020 Queer Emerging Artist Award. Kwaku is also an emerging director, most recently having co-directed the 2nd Year Period Study Project at George Brown Theatre School with veteran director Jeannette Lambermont-Morey, and will return to GBTS this summer to co-direct the 1st Year Shakespeare Scene Study with the visionary Allyson McMackon.

PJ Prudat (she/her) is a Treaty 6 born, proud Michif/Métis/Cree (roots to Batoche, Red River, Qu’Appelle) & French/Scandinavian actor and writer. She holds residencies with the Theatre Centre and Nightswimming and recently with Canadian Stage. PJ has performed as a company actor at the National Arts Centre (English Theatre), the Shaw Festival and in Indigenous~Creative-Led shows extensively across the country. Her maternal 3rd great-grandparents were Buffalo hunters; she loves cake, hats and poetry; and she’d prolly leave it all for the love of a horse.

Jeff Yung (he/him) is a settler on Treaty 13 territory. He is an actor, martial artist, and sometimes poet. Pre-pandemic Jeff appeared in Monday Nights as a member of the 6th Man Collective and in Hong Kong Exile’s Room 2048. Jeff is an avid gamer, anime watcher, movie/tv junkie, basketball fan, and bubble tea lover.

We are so excited to be organizing Unpacking 2020: Deaf Perspectives. Join some amazing panelists and our host, Elizabeth Morris, as they talk about all things 2020, and especially it’s effects on the Deaf Community.

Time: October 8th from 6pm to 7:30pm EST

Location: Zoom! For the zoom link please email info@shakespeareintheruff.com by Oct 8th at 1Pm EST

This is a free event, made possible with generous support from Autism Ontario

Live captions and English Interpretation will be provided.

Hosted by Elizabeth Morris

Elizabeth Morris is a graduate of Washington, D.C’s Gallaudet University for the Deaf and also holds MDes in Inclusive Design from OCAD University. Her thesis was based on creating ways to make live theatre more accessible and inclusive for Deaf and Hard of Hearing audience members, including their families and friends. She won a medal for the best exhibit in her program at OCAD U’s 102nd Graduate Exhibition. Elizabeth is also a professional actor, and has performed in Mexico, Romania, South Africa, Japan and Australia. She was the very first Deaf signing actor at the Stratford Festival, and has performed at the Young People’s Theatre, Theatre Passe Muraille, and Shakespeare Link Canada, National Arts Centre, Concrete Theatre and Citadel Theatre. She is a co-founder of the Deaf Spirit Theatre company. She has performed in

Mustafa Alabssi is a Deaf actor living in Regina, Saskatchewan. Mustafa arrived in Canada from Syria in 2016.He is an actor with Deaf Crows Collective, a Deaf theatre troupe based in Regina. Mustafa has performed in Apple Time at Regina’s Globe Theatre and Edmonton’s SoundOFF Festival. He played the character Ryan alongside co-stars Jaime King, Justin Chu Cary and Kelsey Flower in Netflix’s 2019 hit series Black Summer. Mustafa is a passionate advocate for Deaf rights and accessibility. He hopes to see more Deaf performers involved in theatre and film across Canada and the world.

Natasha is an athlete and artist. She is passionate about mental health, deaf advocacy, fitness and physical expression. Throughout her life, she has nurtured her passion for fitness by competing as

a professional athlete and securing medal positions in both the Deaf Olympics and Pan Am Olympics as well as many other competitive sporting events. While running was her first passion and a means of emotional release, she used acting as a mode of physical expression and found theatre and film to be the preferred spaces for her to thrive as an actor. She has participated in a number of theatre and film productions and has a strong desire to continue to grow and develop as an artist in these industries, expanding representation to include differently-abled persons and empowering Black Deaf women in Canada to shine on and off the stage.

Thurga Kanagasekarampillai is a Deaf Tamil Queer artist. She graduated with Honours in the Acting for Media program at George Brown College in 2018. She has worked as Deaf Interpreter and ASL performer with Cahoots Theatre for ``The Enchanted Loom`` (2016); Red Dress Production for “Drift Seeds” (2017) as ASL performer; Speculation (2018/2019) as ASL performer and Deaf Interpreter; Million Billion Pieces (YTP 2019); The Holy Gasp (July 2020). She is also an actress and was in ‘The Tempest’ at Citadel Theatre as Miranda in Edmonton in April - May 2019. She is the one of three founders of Deafies’ Unique Time with Ali Saeedi, and Ralitsa Rodriguez. Deafies’ Unique Time - ‘Eye So Twisted’ ( Rhubarb Festival / Sound Off Festival 2019) and Deafies Detective Agency (Sound Off Festival 2020).

In 1990, Gary became the first elected Deaf politician in the world, when he served as an NDP Member of Provincial Parliament. He is a provincially and nationally recognized leader with an extensive track record of human rights, anti-discrimination, Deaf and disability advocacy work. Gary graduated with a BA in Social Work and Psychology and MA in Counselling at Gallaudet University in Washington, D.C., and, in 2011, received an honorary doctorate degree from Gallaudet. He has been featured on TV, radio, and in newspapers and magazines nationally and internationally, including the CTV, Global and CBC. He has been the subject of a BBC documentary and a biographical play and book. He is currently writing his Memoirs book.

ASL-English Interpreters:

Carmelle Cachero & Marcia Adolphe

Live Captions:

Sushani Singh

Over the last few months, protesters around the world have been fighting against the systemic racism and violence in our society. We stand with these protesters, and amplify the message that Black lives not only matter, but are valuable and vital. We stand with the movement to fight for a better, more just world for Black People, and recognize that the fight against white supremacy is deep, on-going, and crucial. We are all needed in this movement, and inaction is not an option.

We have spent the past months reflecting on what it means to run a theatre company using the not-for-profit model, magnifying shakespeare. We are interrogating the harm we have caused Black and Indigenous Peoples – the pursuit of a liberated world stands hand in hand with demanding justice for Indigenous Peoples. As a company that produces shakespeare, we are complicit in upholding the supremacy of the white Western canon above any other. Our pursuit of de-centring whiteness needs to go deeper, and we are – and will continue to – examine our mandate, our organization, and our place in the community. Changes, big and small, are necessary, and will be embedded into the company fabric. We are not looking for easy answers or quick fixes, we are in the pursuit of radical justice and peace.

Some of these changes you will see publicly, and some you may only experience if we have the pleasure of working together. What’s important is that these changes occur. We must do better.

One vital part of this process is to open a direct avenue of communication with our leadership and Board of Directors. If any members of our community have questions, we would like to engage in a conversation. If any members of our community would like to discuss past experiences you’ve had with Ruff, in any way, shape, or form, we would like to hear from you. To reach Ruff’s Co-Artistic Directors Eva Barrie and Kaitlyn Riordan, along with Board members Cecile Peterkin and Dasha Peregoudova, email us here. For messages directed exclusively to these two Board members, use this contact form, which, if you choose to do so, can be used anonymously. Any request for confidentiality will be respected.

We want to thank the Black and Indigenous artists who have been fighting this fight for years. We hear you. We support you. Thank you.

We are inspired by and want to thank the countless individuals who are organizing protests, occupies, and artistic expressions to make our city more safe, more vibrant, and more free. That is the city we want to live in, and create art in. Black Lives Matter Toronto, Not Another Black Life, Toronto Prisoners’ Rights Project, Air Rising Collective, and so many more, from the bottom of our hearts, thank you. Please follow these groups on social media to help find a way you can support them.

We recognize these moments are challenging, but we believe that the work we do today, will prepare us for a better tomorrow. And a more just tomorrow is something worth fighting for.

Sincerely,

Eva Barrie & Kaitlyn Riordan

Co-Artistic Directors

August 11th, 2020

Kaitlyn Riordan and Eva Barrie are excited to announce that they will be stepping down as Ruff’s leadership following the summer of 2021. While serving the company for a number of years (Kaitlyn is a founding member, and Eva joined the company in 2016) they have had the opportunity to work with the community that makes Ruff what it is: talented artists, East-End businesses, future game-changers in the training programs, the Board of Directors, long-time audience members, the vibrant Withrow Park community, and the raccoons, who occasionally make cameo appearances and steal the show. That long and incomplete list ensures us that Ruff never was, and never will be, just two individuals. It is a community, a spirit, and a radical love for connection.

Both Eva and Kaitlyn believe that the health of an organization includes bringing in new voices who can refocus and reimagine what’s possible for it. After five and ten years at the helm, respectively, it’s time for a new vision.

This means that Ruff will be seeking new leadership! This city is ripe with amazing potential artistic leaders who can take the company to brave new places, bring new perspectives, and make great art! A full job description, fee, and application guide will be released in the coming days. If you think you are Ruff’s next leader (maybe along with someone else, because hey, shared leadership is what the cool kids do), check back here!

Here’s a photo of Eva and Kaitlyn doing their pre-show speech, which always involved at least four jokes that never got laughs, but that they tested out every night anyway (they once even took a stand-up comedy class with the Young Ruffians . . . this did not help). The next leader(s) will undoubtedly receive many hours of training in How-To-Make-Cringey-AD-Jokes-Between-The-Trees. Please do not be dismayed by this – it’s a vital part of the job

This year was unlike any other before, so we decided to run the Young Ruffian Apprenticeship Program (YRAP) like never before!

Led by Makram Ayache, this year’s program is a paid 8-week playwriting course, where participants from across Canada are digging into some phenomenal ideas and exploring experiences of family, death, belonging, identity, and friendship. Their stylistic investigations also range from conventional structures of the heroic journey to absurdist and magical realism. They are learning the rules of playwriting and daring to break them as they discover, uplift, and amplify their own unique and vital theatrical voices.

Alongside creating with Makram, participants are being mentored by creators Desirée Leverenz, Eva Barrie, and Jay Northcott.

Click here to check out these amazing artists and their work live on August 22nd at 2:00Pm EST.

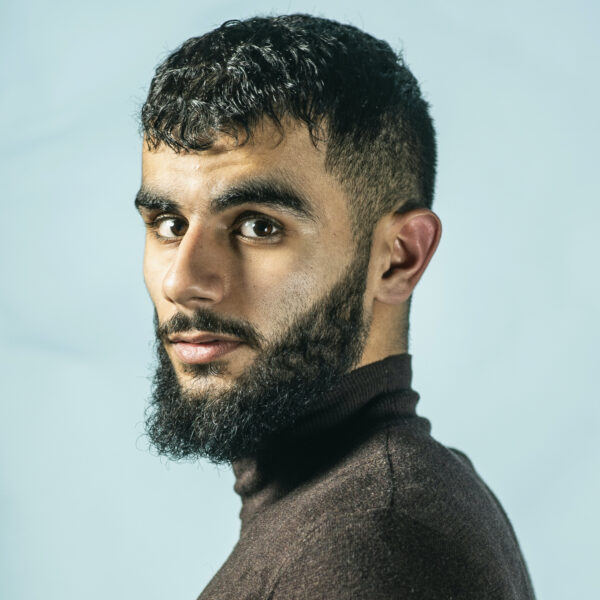

Laith Al-Kinani

Laith Al-Kinani is a theatre artist based out of Toronto. He is in his graduating year as a Performance Acting student at Ryerson University. He has partaken in a myriad of classical, contemporary, and devised productions. When he’s not on stage, he’s having a cold beer by the beach, or watching TikToks with his younger sister.

isi-bhakomen

isi-bhakomen is an Afro-Latinx multi-disciplinary artist with Peruvian and Nigerian heritage. They are entering their final year of acting at The National Theatre School of Canada. Their most recent credits include Black Girl in Search of God, a short film that they wrote, directed and starred in which premiered at the 2019 TIFF Next Wave and Insomniac Film Festival’s Battle of the Scores. Additionally, they were a member of Tarragon Theatre’s Young Playwrights Unit (2019) and Factory Theatre’s The Foundry (2018) where they wrote full-length plays, BOOM! and Mamacha del Carmen.

Kimberly Ho

Kimberly Ho (何文蔚) is a multidisciplinary artist, performer, and collaborator based on the unceded ancestral lands of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish) and Tseil-waututh peoples, known as Vancouver, Canada. In her practice, she seeks to explore and decolonize the intersections of queerness, the physical body, and ancestral history and habits, primarily in the context of Chinese diaspora. Select credits include House and Home (Firehall Arts Centre), Theory (Rumble Theatre), Marathassa (Dance, Vines Festival), No More Parties (Film, Natalie Murao), and A Query (Video installation, VIVO Media Arts Centre), and her short film Dumplings / 餃子 premiering this September 2020 at F-O-R-M (Festival of Recorded Movement). kimberly-ho.com

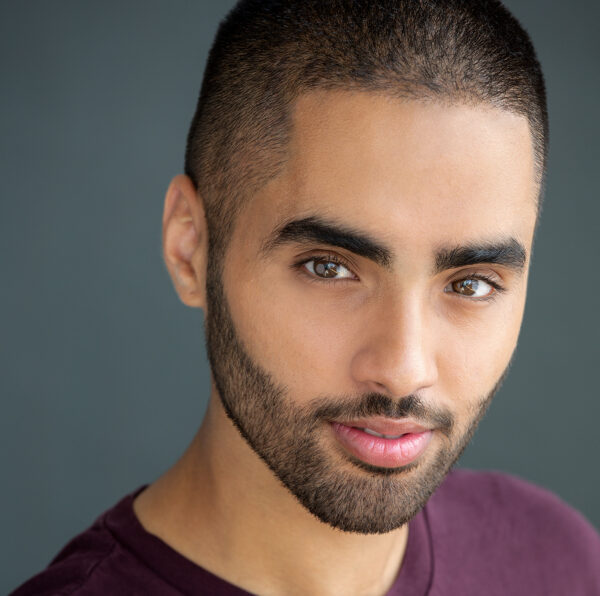

Davinder Malhi

Davinder Malhi is an actor, playwright, and a recent graduate from York University’s Acting Conservatory. His art explores the meeting place between realism and surrealism, with a special focus on bringing South Asian bodies into that space. He hopes to use his process to foster communities that work towards a Brown queer future.

Ziigwen Mixemong

Ziigwen Mixemong is a young Indigenous playwright and author from Beausoleil First Nation. Although playwriting is a relatively new medium for her, she has been raised by her community to be a storyteller. Mixemong has previously written the works entitled Empty Regalia, The Western Door, and 21. Ziigwen strives to place Indigenous voices in the centre of mainstream society’s collective consciousness. Ziigwen is the product of thousands of years worth of resilience and trauma and though she doesn’t always know what to do with it, she tries her best

Are you an emerging artist who wants to keep in the know about all our educational programs and opportunities? Join our mailing list today!

Are you someone who wants to support paid educational opportunities, like the Young Ruffian Apprenticeship Program, and keep them available for future generations? Make a charitable donation and help us support emerging voices!

Desirée is director, creator, and performer living in Tkaronto and hails from Treaty 6. She has an MFA in Theatre from York University (after finishing her undergrad at University of Alberta). She’s the artistic director of The Orange Girls, an experimental performance ensemble that blurs the lines between performance and art (check them out!). Want to see her work up close? She’ll be performing her piece Eat Me at the Rhubarb Festival.

Desirée is director, creator, and performer living in Tkaronto and hails from Treaty 6. She has an MFA in Theatre from York University (after finishing her undergrad at University of Alberta). She’s the artistic director of The Orange Girls, an experimental performance ensemble that blurs the lines between performance and art (check them out!). Want to see her work up close? She’ll be performing her piece Eat Me at the Rhubarb Festival.

To kick off 2020 with our new Associate AD, we asked her a rapid round of 20 Questions. Meet Desirée!

Favourite Shakespeare play?

Today, Othell0

Dream Lady M casting?

Viola Davis!!

Least favourite Shakespeare play?

Midsummer

Favourite park in the world?

The park down the path from where I grew up in St. Albert.

Must have picnic item?

Watermelon!

Super power?

I wish I could read books at warp speed.

Mediocre power?

The power to not put my fire alarm off every time I make toast.

A 2020 resolution?

To learn how to make toast.

Something you miss about Edmonton?

Eating green onion cakes with my sister.

The class/the thing that surprised you the most while doing your Masters at York?

How caring and supportive my cohort was!

A theatre show you’re looking forward to seeing in 2020?

Vivek Shraya’s “How to Fail as a Popstar.”

A favourite piece of advice?

Have a reading routine.

Secret music obsession that you’d never tell anyone about?

Line dancing music. Cadillac Ranch, Cotton Eye’d Joe, etc.

Which basketball team do you support? (hint: this is a trick question)

Duh, Raptors over everything!!! Want to know my least favourite? Phoenix Suns. Their logo is so bad.

Favourite book you read in 2019?

This is very hard for me to say, perhaps I will say an important book I read in 2019 is The Theory of the Young-Girl by a collective called Tiquun.

The thing you most like to cook?

Anything that requires a sauce, I am very good at making sauces.

Place you’d most like to visit?

Morocco!

What would you tell your 20 year old self?

To be brave and make bold choices.

What would you tell your 2 year old self?

To eat bananas, so that you could eat them as an adult. They seem like such a convenient snack, but I hate them.

What excites you most about being a Ruffian?

I’m excited to ask difficult questions, and struggle with answers and solutions with the rest of the Ruff team!

Welcome to a business meeting of your two Ruffian Co-Artistic Directors:

Eva: Hi my friend!

Kaitlyn: Hey Evie B!

Eva: You’re so far away from me at the moment, all the way across the country.

Kaitlyn: Staring at the Rockies covered in mist this morning, very portentous. How’s TO?

Eva: I’m staring to the CN Tower covered in mist. So I guess we’re living in a pretty portentous world. [Eva quickly googles the definition of portentous]

Kaitlyn: We sure are.

Eva: I guess we should start considering what play to do this summer? Though this mist and this PORTENTOUS feeling is making me feel like it’s not summer at all.

Kaitlyn: It does feel like ‘Winter is coming…’. [this is not a plug for HBO]

Eva: Enough about seasons, Kaitlyn, we need to talk about what Shakespeare play we are doing.

Kaitlyn: “Now is the winter of our discontent.”

Eva: We did that one.

Kaitlyn: “Summer’s lease hath all too short a date.”

Eva: Kaitlyn, focus!

Kaitlyn: Nothing is ‘springing’ to mind….sorry.

Eva: I forgive you.

Kaitlyn: Exactly! Forgiveness!

Eva: It’s a powerful act. Some might say a magical act. Have you ever forgiven someone who really hurt you?

Kaitlyn: Yes, and it felt like the biggest release I’ve ever experienced.

Eva: Kind of like you were being released from stone?

Kaitlyn: After what felt like 16 years!

Eva: Was it hard to forgive?

Kaitlyn: I did it instinctually, in that instance, because it was hurting me to hold on to it. So I guess it was harder to hold onto than to forgive, but it took some time. I think our society is weary of forgiveness at the moment though, and maybe I am too?

Eva: I think that’s true. Do you think it’s connected to the fact that we don’t know how to properly repent?

Kaitlyn: Good question. Have you ever repented? Did you know how?

Eva: I have. It took longer than I wish it could have. I needed to really confront who I was, and my actions. That’s a terrifying thing to do. I don’t know if you feel this too, but don’t you think we live in a world where we can never be wrong?

Kaitlyn: I do feel that on a larger level, for anyone other than Donald Trump for some reason, but personally, I am wrong all the time, and somehow, you’re still my friend 🙂

Eva: Even when we have a country in between.

Kaitlyn: Exactly.

Eva: Are you thinking what I’m thinking?

Kaitlyn: Croissants!

Eva: And…

Kaitlyn & Eva: Oh hey Sarah! Fancy seeing you here. Why do you think The Winter’s Tale is perfect for today?

Sarah: Hi Kaitlyn & Eva! Thanks for having me! It’s very fancy to be here!

The Winter’s Tale is a play for us now. It is a fairy tale (improbable things happen), which is another way of saying it is a myth about humanity. Fairy tales are not escapism but doors in the floor into the basement of the human psyche. Isn’t it the perfect time to have a show where we plumb the depths of patriarchy with an eye to coming out the other side by listening to and believing women? And isn’t it interesting to do that on a human artifact that’s hundred of years old, which has been used as a tool of colonialism, which is a container for so many conflicted feelings, to which we owe no undue reverence, which we will bash about to see what is has to say to us now.

This play is also an investigation of inheritance. In a culture that doesn’t know what it has to pass on, and a younger generation that has been violently disinherited and doesn’t know what is rightfully theirs, the intergenerational relationship is one of anxiety.

Eva: Kaitlyn! Maybe we should also tell folks who’s playing Paulina!

Kaitlyn: I think it’s too early for that.

Eva: But it’s so fun!

Kaitlyn: In a month we can announce the whole cast, so let’s not say any-

Kaitlyn & Eva: Jani! Welcome! Why are you excited about this play and this part?

Jani: I am really looking forward to being back in the park. It was such an honour to play Shylock in Merchant of Venice surrounded by the trees, the bats, and the amazing, warm and supportive audiences that attend. I want to continue to be the kind of artist who has something to learn. Rehearsing in the park, playing outside and reaching audiences that are genuinely interested in this kind of theatre experience keep me humble as an actor. I don’t want to ever loose that.

Kaitlyn: I’m pretty excited, Eva. I wish it were summer already!

Eva: No no, I wish it were WINTER.

THE WINTER’S TALE coming to Withrow Park August 2019

We are over-the-moon about our new Youth & Development Coordinator, Darwin Lyons! Darwin’s main role is to run the Young Ruffian Apprenticeship Program, and there’s no one better for the job. Not only was Darwin the Artistic Producer of The Paprika Festival from 2015-2017 (a youth led theatre festival and year round training/mentorship program for young artists), she also created the inaugural Acting program at Centauri Arts, and was a facilitator at Heydon Park Secondary school, a school that proudly uses alternative models of learning for women. We can’t wait to see what she does she with Young Ruffian Program!

We are over-the-moon about our new Youth & Development Coordinator, Darwin Lyons! Darwin’s main role is to run the Young Ruffian Apprenticeship Program, and there’s no one better for the job. Not only was Darwin the Artistic Producer of The Paprika Festival from 2015-2017 (a youth led theatre festival and year round training/mentorship program for young artists), she also created the inaugural Acting program at Centauri Arts, and was a facilitator at Heydon Park Secondary school, a school that proudly uses alternative models of learning for women. We can’t wait to see what she does she with Young Ruffian Program!

Here’s some rapid-fire questions for Darwin:

What’s your favourite Shakespeare play?

A Midsummer Night’s Dream

Which, in your opinion, is the most over-rated Shakespeare play?

Macbeth

What are you most excited for in the Young Ruffian Program?

I’m excited to see the work the Young Ruffians come up with – every time I work with people in that age group the work fascinates and inspires me

What’s a book/movie/poem/show/play you turn to when you need inspiration?

Mary Oliver’s When Death Comes

What inspired you as a teenager?

As a teenager I was really inspired by my peers. I remember feeling like the people around me were so smart and strong, and like we had this amazing potential to make change.

Describe your role with Ruff in less than three words.

Circle learning

Best thing about Withrow Park?

Beautiful, huge nature in the middle of the city, a wonderful community of people and a very large hill that makes me a better biker

A little known fact about you that surprises people:

I don’t like mushrooms

If you could have a super power, what would it be?

Be able to communicate in the language of whoever I am with

If you could have a mediocre power, what would it be?

To learn new skills very quickly

To apply for our Young Ruffian Program, check back here in the Spring, or follow us on Instagram! (@shakespeareruff)