This year was unlike any other before, so we decided to run the Young Ruffian Apprenticeship Program (YRAP) like never before!

Led by Makram Ayache, this year’s program is a paid 8-week playwriting course, where participants from across Canada are digging into some phenomenal ideas and exploring experiences of family, death, belonging, identity, and friendship. Their stylistic investigations also range from conventional structures of the heroic journey to absurdist and magical realism. They are learning the rules of playwriting and daring to break them as they discover, uplift, and amplify their own unique and vital theatrical voices.

Alongside creating with Makram, participants are being mentored by creators Desirée Leverenz, Eva Barrie, and Jay Northcott.

Click here to check out these amazing artists and their work live on August 22nd at 2:00Pm EST.

The Young Ruffians

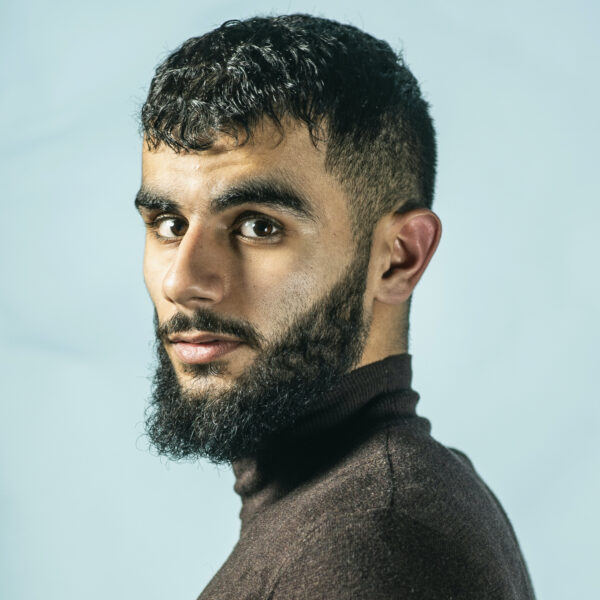

Laith Al-Kinani

Laith Al-Kinani is a theatre artist based out of Toronto. He is in his graduating year as a Performance Acting student at Ryerson University. He has partaken in a myriad of classical, contemporary, and devised productions. When he’s not on stage, he’s having a cold beer by the beach, or watching TikToks with his younger sister.

isi-bhakomen

isi-bhakomen is an Afro-Latinx multi-disciplinary artist with Peruvian and Nigerian heritage. They are entering their final year of acting at The National Theatre School of Canada. Their most recent credits include Black Girl in Search of God, a short film that they wrote, directed and starred in which premiered at the 2019 TIFF Next Wave and Insomniac Film Festival’s Battle of the Scores. Additionally, they were a member of Tarragon Theatre’s Young Playwrights Unit (2019) and Factory Theatre’s The Foundry (2018) where they wrote full-length plays, BOOM! and Mamacha del Carmen.

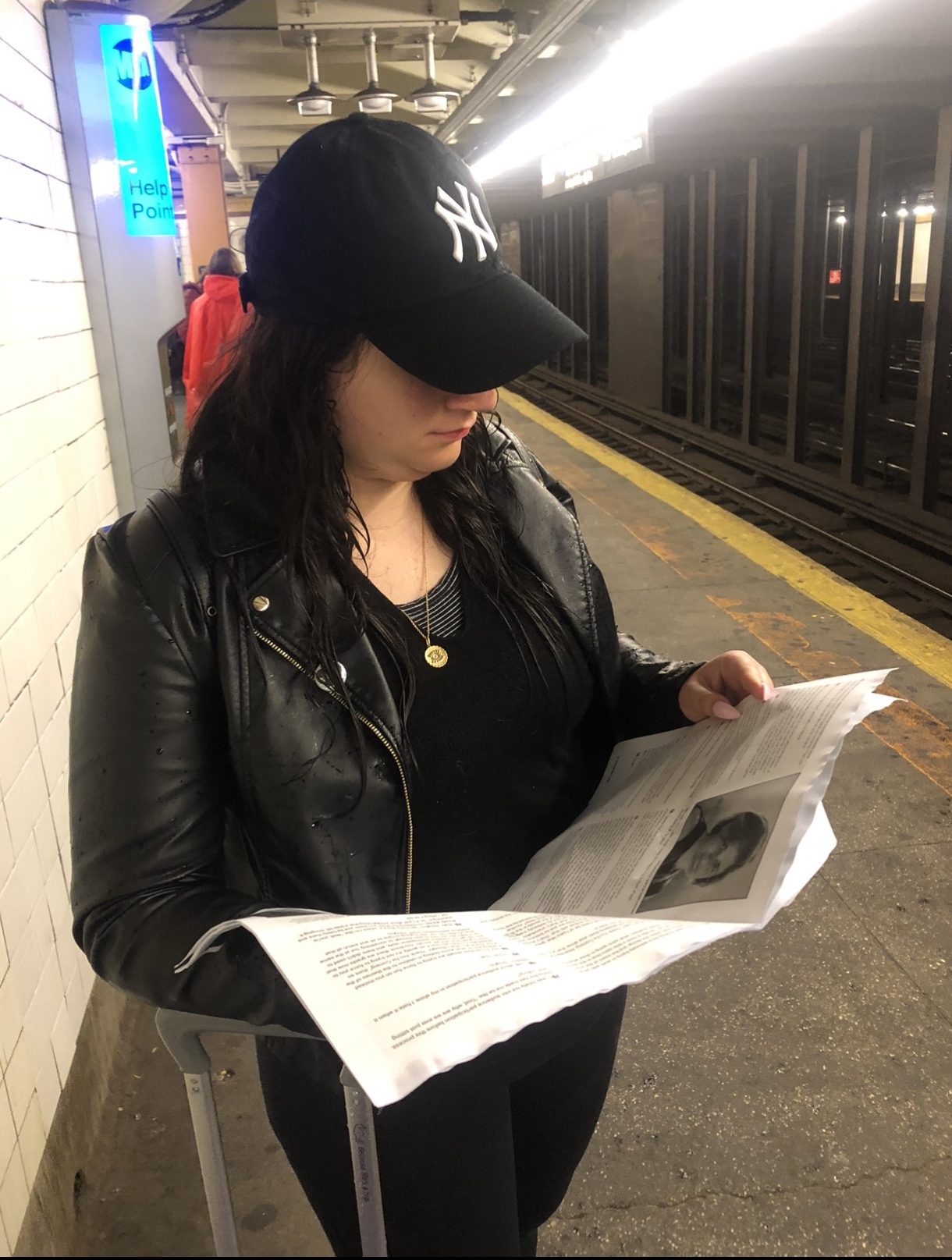

Kimberly Ho

Kimberly Ho (何文蔚) is a multidisciplinary artist, performer, and collaborator based on the unceded ancestral lands of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish) and Tseil-waututh peoples, known as Vancouver, Canada. In her practice, she seeks to explore and decolonize the intersections of queerness, the physical body, and ancestral history and habits, primarily in the context of Chinese diaspora. Select credits include House and Home (Firehall Arts Centre), Theory (Rumble Theatre), Marathassa (Dance, Vines Festival), No More Parties (Film, Natalie Murao), and A Query (Video installation, VIVO Media Arts Centre), and her short film Dumplings / 餃子 premiering this September 2020 at F-O-R-M (Festival of Recorded Movement). kimberly-ho.com

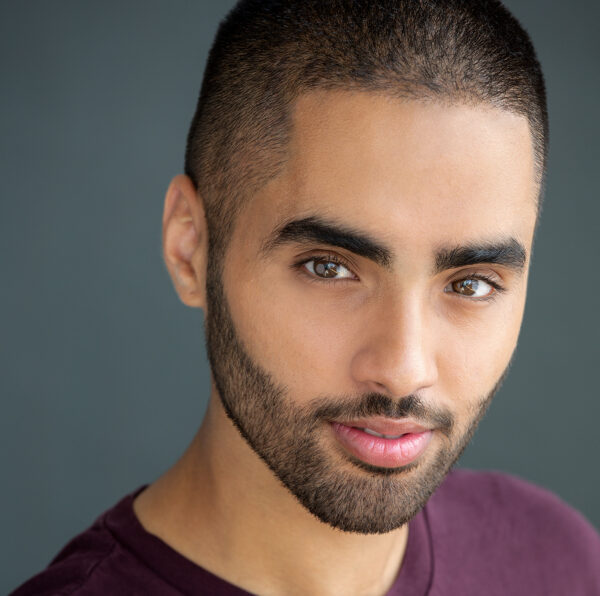

Davinder Malhi

Davinder Malhi is an actor, playwright, and a recent graduate from York University’s Acting Conservatory. His art explores the meeting place between realism and surrealism, with a special focus on bringing South Asian bodies into that space. He hopes to use his process to foster communities that work towards a Brown queer future.

Ziigwen Mixemong

Ziigwen Mixemong is a young Indigenous playwright and author from Beausoleil First Nation. Although playwriting is a relatively new medium for her, she has been raised by her community to be a storyteller. Mixemong has previously written the works entitled Empty Regalia, The Western Door, and 21. Ziigwen strives to place Indigenous voices in the centre of mainstream society’s collective consciousness. Ziigwen is the product of thousands of years worth of resilience and trauma and though she doesn’t always know what to do with it, she tries her best

Are you an emerging artist who wants to keep in the know about all our educational programs and opportunities? Join our mailing list today!

Are you someone who wants to support paid educational opportunities, like the Young Ruffian Apprenticeship Program, and keep them available for future generations? Make a charitable donation and help us support emerging voices!